A Cappadocian Father on Divine Sovereignty: The Pneumatology of Gregory of Nazianzus (329-389)

29 August 2023

By Dr. Adi Schlebusch

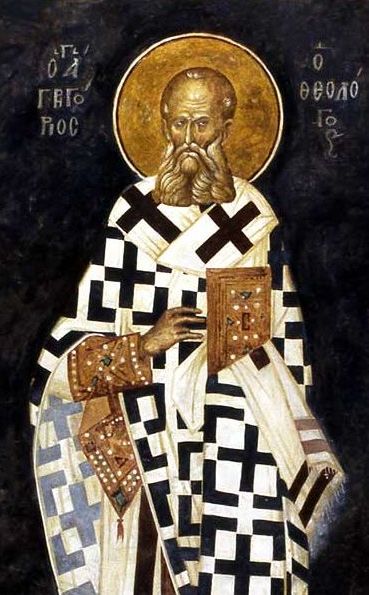

In the fourth century AD, three highly influential patristic fathers from the same region, Cappadocia, today known as Central Anatolia in Turkey, together became known as the Cappadocian Fathers. They were Basil the Great (330-379), Gregory of Nyssa (335-395), and Gregory of Nazianzus (329-389). I only very recently discovered how much the latter of these three wrote about the sovereignty of God, and how much he emphasized sovereign grace—especially when writing about the Holy Spirit—a discovery I would like to share with the reader in this piece.

Gregory of Nazianzus was born in 329, just four years after the all-important Council of Nicea, and widely achieved renown for his important works on the Trinity, and especially his doctrine of the Holy Spirit, also known as Pneumatology. During the Council of Constantinople in 381, he also briefly served as bishop of that city.1 At this important council, Trinitarian orthodoxy and especially orthodox pneumatology was upheld against various errors. As R.J. Rushdoony explains:

Constantinople emphasized the reality of the Trinity, of one God and three Persons. Instead of an abstract concept of original substance, the Council affirmed a very personal God. Instead of a silent God, the Council declared the God of revelation ... The Pneumatomachi[‘s] denial of the deity of the Holy Ghost was a denial of the immanence of God. Thus, even if they had been orthodox in their doctrines of the Father and the Son ..., they still would have left God irrelevant because unrelated to this world. God would have been the “wholly other” who could not truly reveal Himself to man or operate in the universe. This absolutely transcendent god would be a hidden god, a god without revelation and wholly cut off from man ... Constantinople in 381 A.D. spelled out the certainties of the faith against attempts by humanism to render it uncertain.2

Gregory’s exceptional influence upon this council and the development of trinitarian theology in general is evidenced by the fact that the Council of Chalcedon in 451 awarded him with the official title “The Theologian”—a title which until that time had only been awarded to John the apostle.3

Throughout Gregory's writings, he boldly defends the divinity of the Holy Spirit. He also amplifies that God’s work of grace through the Divine Person of the Holy Spirit is not dependent upon human consent, but that the Spirit not only gives faith itself, but also the will to accept that gift. If God loves you and wants to make you part of his family through the power of the Holy Spirit, He is necessarily going to accomplish that. With Gregory there is no doubt that salvation is, from start to finish, a gift of a sovereign God without any merit on the part of man.4 The work of the Holy Spirit in working regeneration in the hearts of the elect he also describes as “a changing of one’s life and a liberation from the bonds of slavery, as well as a transformation of the elements from which our nature is constituted.”5 He then proceeds to amplify that it is “the Holy Spirit which effectuates spiritual regeneration and ... no one will see the kingdom unless they are renewed by the Spirit.”6

Commenting on Romans 9:16 he also notes that “even the act of choosing for God is a gracious gift from God Himself ... since the will to choose is itself a gift of God, Paul attributes everything to God.”7 Gregory makes it clear that, like Philippians 2:13 also teaches, it is the Holy Spirit which works in us the will or desire to commit to Christ as Lord and Savior.

Gregory’s view on the sovereignty of God in our salvation is wholly in line with what the Bible and the Reformed Confessions teach. Although our fallen nature necessitates that we would, of our own accord, always choose against God, he also highlights that we aren’t merely passive in our reception of the gift of faith, since faith is something we need to make our own. Yet we can only accept this gift willingly when we receive the grace of God the Holy Spirit which enables us to do so.

1. John A. McGuckin, 2001. Gregory of Nazianzus: An Intellectual Biography (St Vladimir’s Seminary Press: Crestwood, NY), p. xxiv.

2. R.J. Rushdoony, 1998. The Foundations of Social Order: Studies in the Creeds and Councils of the Early Church (Ross House: Vallecito, CA), p. 21, 23.

3. McGuckin, p. xxv.

4. Steven J. Lawson, 2011. Pillars of Grace, AD 100-1564: A Long Line of Godly Men (Reformation Trust: Orlando, FL), p. 160.

5. Gregorius Nazianzus, 2008. Festal Orations (St Vladimir’s Seminary Press: Crestwood, NY), p. 100-101.

6. Ibid., p. 156.

7. Gregorius Nazianzus. 2007. Oration 37.13, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, vol. VII (Cosimo Classics, New York), p. 341-342.