Christian Nationalism and the Churches of England and Scotland

31 May 2023

By Dr. Adi Schlebusch

In the years following the Reformation, a battle between Roman Catholics and Protestants raged in England with regard to the national religion of the English nation. It was commonly agreed at the time, that, in accordance with the Biblical-covenantal paradigm for people groups, a nation has to be united in confession, lest that nation dissolve into disarray and chaos. Indeed, the modern history of the failed post World War II projects of multiculturalism and pluralism has also shown this position to accord with reality, especially in light of the rise of Cultural Marxism to become the dominant or de facto established religion in most Western nations.

When Elizabeth I, a Protestant monarch, ascended to the throne of England in 1558, many English Roman Catholics were highly displeased and regarded Mary Stuart, the Roman Catholic queen of Scotland and most senior descendent of Henry VII (who ruled from 1485-1509), to be the rightful monarch over both nations.1 At the time, most of the magistrates and clergy were still Roman Catholic, with Calvinists only being dominant in London and southern England. For the English Reformers, the fight for their national good and the fight for the true faith went hand in hand. As bishop John Aylmer proclaimed in 1558: "God is English. For you fight not only in the quarrel of your country, but also and chiefly in defense of His true religion and of his dear Son Christ."2

What English Protestants envisoned was a complete reformation of the English national life with a Protestant monarch, a Protestant national church, a Protestant culture, Protestant education and the application of a Christian worldview to all fields of science. In 1571 English theologians therefore emerged with a new national creed for its national church, following Elizabeth's formal excommunication from the Roman Catholic Church by pope Pius V.3 This became known as the 39 Articles of Religion.

In Scotland, Mary Tudor, Elizabeth's predecessor, had also been known as Bloody Mary because of her extremely violent and brutal persecutions of Calvinists. This of course forms the background to John Knox's publication of his First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women in 1558. The year before, a group of Protestant Scottish nobles, calling themselves The Lords of the Congregation of Jesus Christ, had gathered at Edinburgh and signed what what become known as the First Scottish Covenant, in which they committed themselves to reforming Scottish national life in accordance with the Reformed religion.4

Mary Stuart, the queen of the Scots, had other ideas, however, and she hoped to sever the alliance between Scottish Protestants and the English monarchy, while forming an alliance with the Roman Catholic minority in England.

Knox's preaching in Scotland initiated what could be described as a religious revolution, which ultimately culminated the Scottish parliament establishing Calvinism as official national religion in 1560. Mary Stuart eventually abdicated the throne in 1567.5

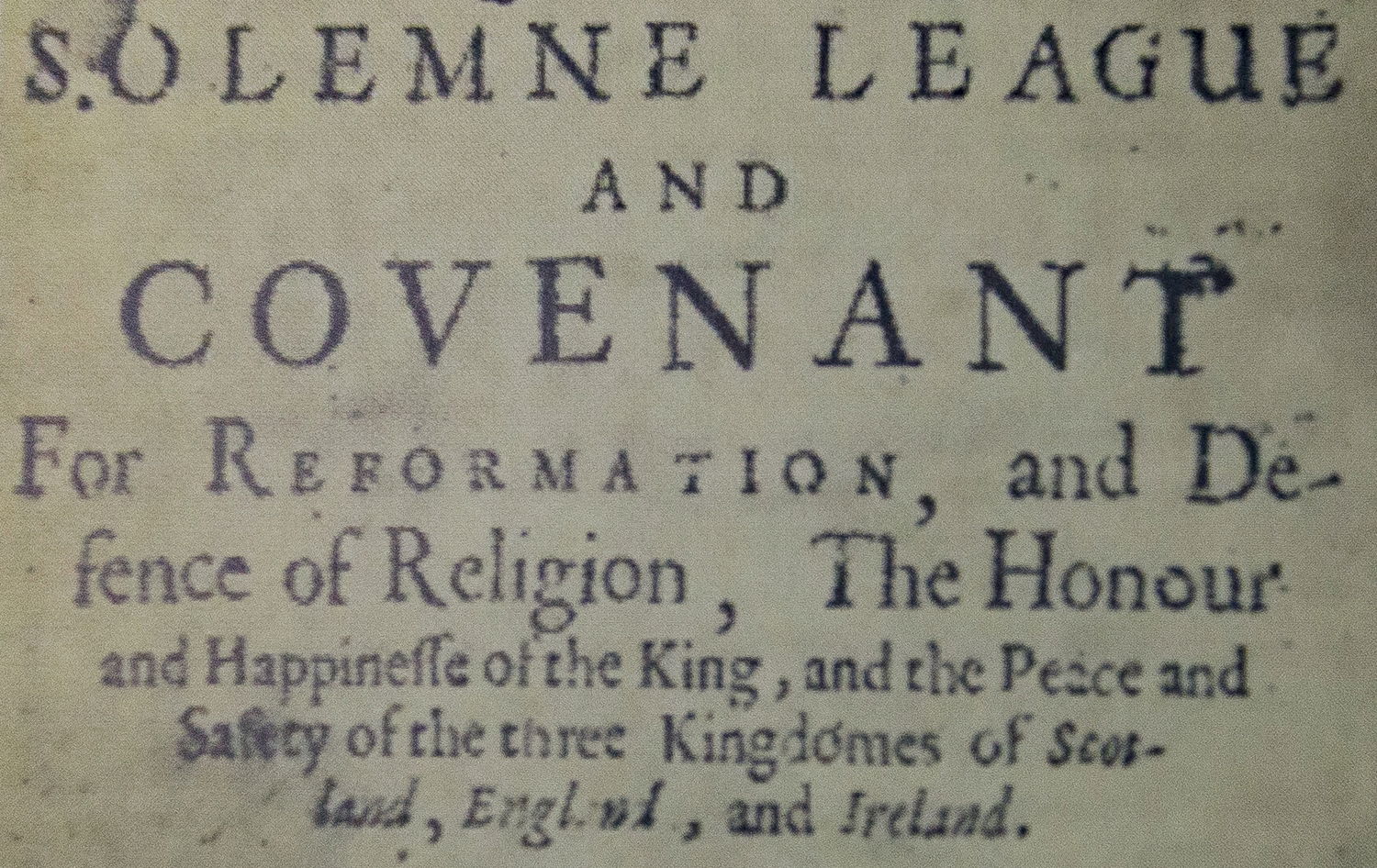

With the Churches of Scotland and England having been established, one of the chief purposes of the Westminster Assembly (1643-1653) was to bring the English Church into closer conformity with the Scottish Church so as to strenghten the alliance between the two nations, both of whom sought to maintain their Protestant Christian Nationalism over against the imperialist aspirations of Rome as manifested in the tyrannical policies of king Charles I.6 The background to the assembly was the English people looking towards their Scottish brethren for help in their fight for national self-determination, to which the Scots agreed on the condition that they subscribe to a religious covenant aimed at bringing the national creeds of the these nations nearer to one another, while at the same time maintaining the distinct liberties of each kingdom, and bringing England into a national covenant with God. This covenant became known as The Solemn League and Covenant of 1643.

The Solemn League and Covenant was also signed by the first Scottish Presbytery which had just been established in Ireland in 1641. This was accompanied by a national repentance of the Scots-Irish people. As the Presbyterian historian Patrick Adair points out: "The covenant was taken in all places with great affection; partly with sorrow for former judgments and sins and miseries ... and partly with joy under present consolation, in the hopes of laying a foundation for the work of God in the land."7

Sadly, and as we all too well know, in the aftermath of Enlightenment, both the Church of England as well as the Church of Scotland adopted theological liberalism and moved away from their historical origins in the Christian Nationalism of the English and Scottish peoples.

Today, the ideas of Christian Nationalism as it has historically manifested on the British Isles continue to be adhered to by the Free Church of Scotland, the Free Church of Scotland (Continuing) as well as the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Ireland. As outlined in an article by Rev. John Macleod the Free Presbyterian Magazine in April 2001:

The Establishment Principle, or the Principle of the National Recognition of Religion, maintains the scriptural view of the universal supremacy of Christ as King of nations as well as saints, with the consequent duty of nations as such, and civil rulers in their official capacity, to honour and serve Him by recognizing his truth and promoting his cause.

He continues:

Christ is King of nations as well as King of saints and ... [as such] we are advocates for a national recognition and support of religion—we are not voluntaries.

Finally, it is clear that the Solemn League and Covenant, as a national covenant, continues to be understood by the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland as binding upon posterity, being the continuation of the Scottish nation, since "in Scripture, one does see social covenants that morally oblige successive generations, but there is no obligation, or example, of all descendents to each individually swear to that social or national covenant." Likewise the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Ireland, a denomination made up of Ulter-Scots, acknowledges that "those who first swore the Solemn League and Covenant intended that it should bind them and future generations, 'that we and our posterity after us may as brethren live in faith and love'."

It is for this reason the Free Church of Scotland, Free Church of Scotland (Continuing), and Reformed Presbyterian Church of Ireland do not oblige incoming office bearers to re-swear the covenant—a testimony to these denominations' commitment to maintaining ecclesiastical practices in accordance with the Biblical idea of the nation as ethnos defined by lineage, and in contradistinction to the liberal idea of propositional nationhood.

1. Weir, A. 2003. Mary, Queen of Scots and the Murder of Lord Darnley. London: Random House, p. 18.

2. Aylmer, J. 1559. Harbor for Faithful and True Subjects, p. 4.

3. Haynes, A. 2004. Walsingham: Elizabethan Spymaster and Statesman. Stroud, England: Sutton Publishing. p. 13 .

4. Scott, O. 1991. The Great Christian Revolution. Vallecito, CA: Ross House, p. 153.

5. Cowan, H. 1906. John Knox: The Hero of the Scottish Reformation. London: Putnam, p. 306.

6. Leith, J.H. 1973. Assembly at Westminster: Reformed Theology in the Making. Richmond, VA: John Knox Press, p. 26.

7. Adair, P. 1866. A True Narrative of the Rise and Progress of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland (1623-1670). Belfast: Aitchison, p. 103.