Herman Dooyeweerd and Neo-Calvinist Liberalism

19 July 2025

By dr Adi Schlebusch

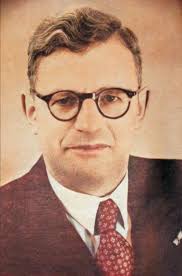

When it comes to twentieth-century Christian philosophers, few figures loom as large as Herman Dooyeweerd (1894-1977), a Dutch thinker whose insights into the axiomatic nature of human thought had a profound impact on the landscape of Calvinist philosophy. Renowned for his rigorous articulation of the Christian worldview, Dooyeweerd’s contributions to philosophy, particularly in the realm of law, established him as a luminary whose ideas reverberated far beyond his native Netherlands. Yet it must be said that some of his theological positions, particularly his theory of time, have halped to sow seeds of twentieth-century liberalism that undermined the very orthodoxy he was supposed to uphold. The purpose of this article is to explore Dooyeweerd’s philosophical contributions, while critically evaluating his legacy and influence.

From 1926 to 1965, Dooyeweerd served as a professor of philosophy of law at the Free Universitury Amsterdam, leaving an indelible mark on Christian scholarship in the Netherlands and beyond. His work is characterized by his bold commitment to the idea that all human thought is underpinned by presuppositions or pre-theoretical axioms that carry a distinctly religious significance. As he famously argued, these presuppositions reflect the innate human impulse to direct itself toward the absolute origin, source, and cause of all meaning. Dooyeweerd rightly maintained that presuppositions or pre-theoretical axioms underpin all human thought and that these presuppositions, by virtue of their epistemological nature and as spiritual driving forces impelling any thinker to interpret reality through its lenses, have a distinctly religious significance, a principle that underscores his commitment to a Christocentric worldview. These axioms, being pre-theoretical and non-demonstrable commitments taken in faith, position human thought as inherently oriented toward God, the ultimate source of meaning.1

Dooyeweerd’s philosophy aligns with the Neo-Calvinist tradition, which seeks to apply a Christian worldview to all spheres of life. His emphasis on the religious nature of presuppositions provided a robust framework for understanding reality through the lens of divine revelation. By asserting that all thought is shaped by faith-based commitments, Dooyeweerd challenged the secular notion of “neutral” science, which he viewed as a myth that obscures the spiritual underpinnings neccessary to enable intellectual inquiry. His work thus served as a clarion call for Christians to engage in scholarship that acknowledges Christ’s sovereign lordship over every domain of knowledge. By framing all human thought as inherently religious, Dooyeweerd equipped Christian scholars to engage with the sciences without conceding to the false neutrality of modernist ideologies.

Yet despite his monumental contributions, Dooyeweerd’s legacy is complicated by a serious theological misstep that inadvertently paved the way for liberal influences within Christian thought. Specifically, his adoption of a neo-orthodox antithesis between time and eternity, particularly as this manifested in his categorization of the creative days in Genesis 1, which he interpreted as belonging to the “pistical sphere,” the realm of faith, as opposed to the “scientific sphere.” By means of this distinction he fundamentally undermined the authority of Scripture as authoritative special revelation. Dooyeweerd inherited this neo-orthodox antithesis between time and eternity, inherited from Barth, who famously often contrasted eternity (God’s timeless reality) with historical time (the human experience of temporality). He treated biblical narratives, including Genesis, as theological witnesses to God’s revelation rather than historical or scientific accounts. As G.K Berkhouwer rightly pointed out, Barth advocated the heresy of Christonomism, fundamentally underminging the doctrine of revelation denying the divine nature of any revelation outside Christ’s historical incarnation.2

While Dooyeweerd did not fall into the heresy of Christonomism itself, his distinction between eschatological and cosmic time, especially in characterizing the creative days mentioned in Genesis 1 as an example of the former, introduced a serious error into his philosophical system. As the American Calvinist philosopher Gordon Clark noted in response to Dooyeweerd's errors: “If any part of the Bible events are beyond the limits of cosmic time … how does one decide which of the Biblical accounts are historical and which are not? If the six days of creation are not temporal, is the serpent’s temptation of Eve historical? And is the crucifixion historical?”3

This theory of time, which separated the biblical account of creation from scientific inquiry, constituted a departure from the orthodox Calvinist view that holds Scripture as infallible across all spheres of knowledge. By relegating Genesis 1 to the pistical sphere, Dooyeweerd weakened the unity of special and general revelation. And while Dooyeweerd was not a liberal, sadly, the seeds of liberalism were already present in his theory of time. Dooyeweerd's philosophical framework, though rooted in a desire to uphold Christian truth, inadvertently provided an opening for the erosion of biblical authority, particularly in a post-war academic context where liberalism was gaining ground.

1. Dooyeweerd, H. 1935. De wijsbegeerte der wetsidee. Boek I: De wetsidee als grondlegging der wijsbegeerte. Amsterdam: H.J. Paris, p. 21, 24.

2. For an overview of Berkhouwer's critique of Barth, see Echeverria, E. 2013. Berkouwer and Catholicism. Leiden: Brill, p. 123-124.

3. Clark, G. 1956. "Cosmic Time," The Gordon Review Vol. II No. 3.