Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos on the Nation as a People

27 December 2024

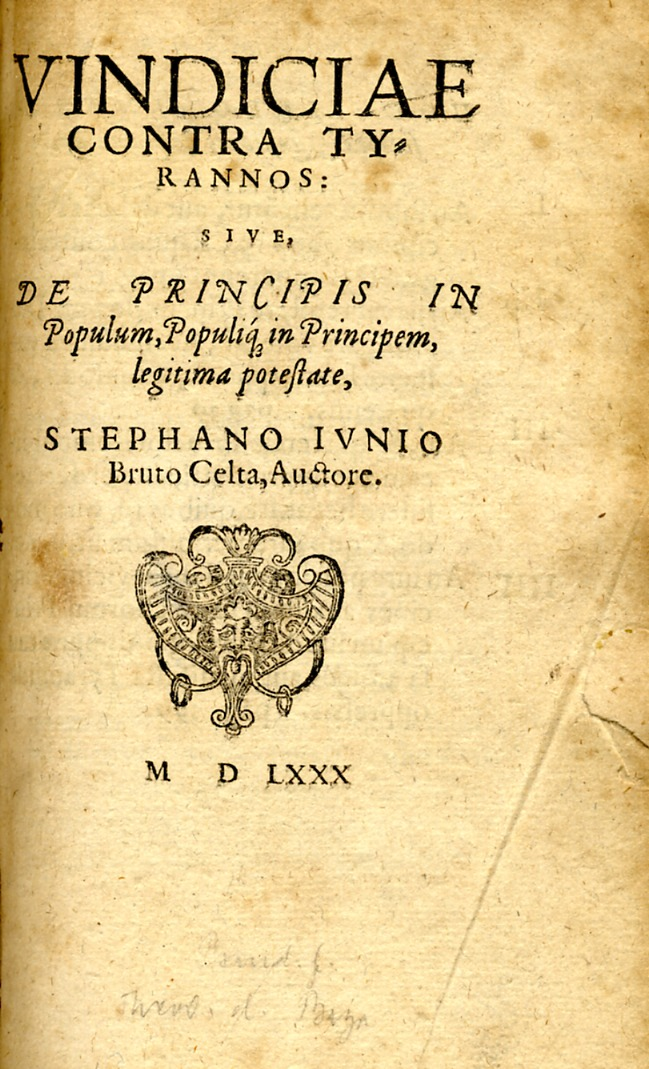

Vindiciae contra tyrannos (Defense of Liberty Against Tyrants) is a significant work of political thought published under the pseudonym Junius Brutus in 1579, at the high of the French Wars of Religion. Within a context marked by intense religious and political strife, the treatise served as a defense of resistance to unjust rulers or tyrants who overstep the limits of their authority. The book offers a framework for evaluating the legitimacy of rulers and justifying resistance, even armed rebellion, when they act tyrannically, emphasizing the idea that rulers derive their authority from God and the people and as such must be held accountable by both. The Vindiciae serves as one of the most important historical sources for Protestant political theory and maintains a covenantal or federal approach to governance and statehood throughout.

Authorship of the Vindiciae has long been debated. Traditionally attributed to Philippe du Plessis-Mornay, a prominent Huguenot leader, and sometimes to Hubert Languet, a Protestant scholar and diplomat, the precise identity of the author remains uncertain. Both men were key figures in the Huguenot resistance movement, which sought to protect Protestant communities against Catholic persecution. The anonymity of the work, coupled with its radical political ideas, underscores the danger such a publication posed to its writer in the fraught political climate of the late sixteenth century.

In the third section of the book, the rights and duties of rulers towards their subjects are discussed at great length, with the author appealing to both biblical and historical examples to highlight the practical significance of the principles of governance outlined in the first two sections. One of the aspects discussed in this chapter is the fact that rulers do not in any way possess ownership of a kingdom but are to rule as stewards on behalf of the people and in obedience to God. As such, rulers are covenantally responsible to both.

One of the implications of this principle as outlined in the Vindiciae is the fact that rulers do not have the right to sell or hand over their realm or any part of it a third party. Various examples are listed of medieval kings who illegitimately handed certain towns or counties to other lords or kings, and how these illegitimate acts were often declared unlawful either by parliaments, the aristocracy, or their successors. The author of Vindiciae then goes on to note that these examples prove that a government has no legitimate right to hand over a realm or any part of it, "since a kingdom consists of a nation (populo) and not of dirt or walls. A free people cannot be sold ... The subjects of a ruler are not his slaves, but his brothers (fratres), and that not each individually, but as a whole, and the nation must therefore be regarded as lord (dominus) of the kingdom."

The word populo can mean either "population" or "nation," but its meaning in this particular context is clarified by the reference, in this same paragraph, to the same group of people as the ruler's fratres (brothers). From this we can derive that the principle of kin-rule is presupposed as normative here. In other words, the ruler must be ethnically related to the people he rules. Secondly, propositional nationhood and propositional covenantalism are absolutely shattered by Vindiciae's definition of a nation as essentially consisting of families of kinsmen according to the flesh, rather than whosoever may find themselves on a certain territory at a given time. A nation is not an economic zone or a job market, it is an extended family bound together by kinship and ancestry and as a covenantal unit, it occupies and inhabits a territory or political realm providentially appointed to it by God.

Finally, it must also be noted that the principle that a ruler must rule on behalf of a nation defined ethnically, and that he has no right to hand over any part of their national homeland to foreigners, means that mass immigration or importation of a people ethnically foreign to the native population by defintion amounts to tyranny, since it is not the government, but the people or ethnos of a land that is its true lord or dominus. As the Counter-Enlightenment German Lutheran philosopher-theologian Johan Gottfried Herder (1744—1803) noted with regard to the character of nationhood:

The most natural state is, therefore, one nation, an extended family, with one national character. This it retains for ages and develops most naturally if the leaders come from the people … Nothing, therefore, is more manifestly contrary to the purposes of political government than the unnatural enlargement of states, and the wild mixing of various races and nationalities under one scepter.1

Historic Protestant political theory clearly teaches ethno-nationalism as the application of Kinist principles to the political domain.

1. Herder, J.G. 1820. Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit. Stuttgart: Cotta, p. 298. “Die Natur erzieht Familien; der natürlichste Staat ist also auch ein Volk, mit einem Nationalcharakter. Jahrtausende lang erhält sich dieser in ihm und kann, wenn seinem mitgebor: nen Fürsten daran liegt, am Natürlichsten ausgebildet werden … Nichts scheint also dem Zweck der Regierungen so offenbar entgegen als die unnatürliche Vergrößerung der Staaten, die wilde Vermischung der Menschengattungen und Nationen unter Einem Scepter.”